Builders and Destroyers... The History of the Moroccan Quarter in Jerusalem

Awni Fares

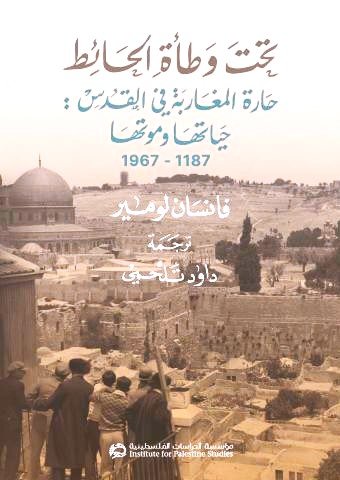

The history of the city of Jerusalem has occupied a part of the interests of the Institute for Palestine Studies. Over the past decades, it has published a number of books and studies that dealt with the history of the city, its neighborhoods, its people, and the major challenges it faces. The Moroccan Quarter and its surroundings were at the heart of this interest. A few years ago, the Institute published an important book by the Jerusalemite historian Nazmi al-Jubeh.[1] A major part of it focused on the Moroccan Quarter. The book we are discussing in this text is "Under the Wall: The Moroccan Quarter in Jerusalem: Its Life and Death 1187-1967," by French author Vincent Lemire and translated by David Talhami.

The author is a fifty-year-old historian from Paris, of Belgian origin. He is a university lecturer, a history specialist, and a documentarian, primarily interested in the history of Jerusalem. He earned his doctorate for his thesis on the water history of Jerusalem. He has published several books on the city, including “The History of Jerusalem,” a novel in which an ancient olive tree tells the story of the city over 4,000 years. The book is supported by illustrations. He runs the “Open Jerusalem” project, which aims to catalog tens of thousands of historical documents related to the city of Jerusalem and make them available in several languages. It is worth noting that he has issued a bold position in which he condemned the genocide in the Gaza Strip, supported France’s intention to recognize the Palestinian state, and called for a boycott of Israel to deter it from its crimes.[2]

About the book:

This book, published in 2024, is the result of five years of continuous effort, during which Lemaire dug into more than fifteen archives, including the archives of the Sharia Court in Jerusalem, the archives of the Waqf in Turkey, the Zionist archives, the royal archives in Rabat, the archives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the archives of the Middle East Center in Oxford, in addition to the contents of four historical libraries in Palestine and France. He also benefited from a long list of references, including hundreds of books and studies in multiple languages, and from a long line of assistants, both male and female.

The book is the culmination of a journey through a “told story,” a “sensitive and fragile,” “flaming and painful” history, obscured by the “shadows cast” by a “heavy” adjacent wall, “literally surrounded by walls,” and “cornered.” At the same time, it is a “Mediterranean” history filled with stories of migrations, pilgrims, refugees, and saints, a “colonial” history, with French interventions under the pretext of protecting Moroccans, and a history of conflict with the Zionist project, from the Zionists’ attempts to buy the neighborhood until its destruction and the displacement of its people. Despite all of this, the serious historian is required to “mobilize all the exploratory and moral requirements simultaneously,” while trying to save this history from “this stifling juxtaposition.”[3] The book also takes a serious look at archives, providing an interesting discussion of their location, the number of documents they contain, their indexing methods, their date of publication, their contents, their uses, and the impact of local, regional, and international developments on them.

The book is 485 pages long and includes an introduction, a preface, six chapters, a conclusion, a list of sources and references, an index, 65 panels including photographs, and copies of excerpts from documents including letters, decisions, lists, postcards, and other items.

Photos from the history of urban development in Palestine... about the founding of the Moroccan Quarter and its golden age:

The establishment of the Moroccan Quarter is part of the history of Islamic urban development in our region. The Islamic era witnessed the emergence of new cities and the expansion of existing ones. After the liberation of Palestine from the Frankish invasion, the issue of urban development occupied a large part of major public and official projects. Construction and housing work encompassed several cities and towns, including Jerusalem, whose urban space was redrawn by the liberating leaders. The city remained a focus of attention for the sultans and great leaders, who preserved its social and institutional structures, at the heart of which was the Waqf institution, which played a major role in overseeing the various affairs of Jerusalemites.

According to Lemaire, the history of the Moroccan Quarter began in 1187 when King Al-Afdal Ali, the eldest son of Saladin, and Sidi Abu Madyan, a Sufi of Andalusian origin, took the initiative to establish an Islamic endowment to care for pilgrims from the Maghreb passing through Jerusalem, as part of a major initiative aimed at rebuilding the city. The endowment document was later drawn up by one of Sidi Abu Madyan’s grandsons in 1320, to form the legal basis for the quarter, taking into account that Abu Madyan’s endowment is not the oldest.[4] But it is the most documented, the richest, and the most contributing to securing the needs of the neighborhood's residents, and it is the one after which all the endowments will be named.

According to the author's vision, the neighborhood experienced its golden age during the Ottoman rule, which witnessed a strengthening of the status of the Waqf and its legal and financial capabilities. There are interesting details extracted from documents of the Sharia Court in Jerusalem, concerning the three main properties of the neighborhood's Waqf: the lands of Ein Karem, the Moroccan Quarter, and its Zawiya. In addition, there is a list of Waqf properties inside and outside Jerusalem, including a group of warehouses, houses, orchards, lands, and more.

The Ottoman central archives revealed a high level of support and backing for the Abu Madyan waqf from Ottoman rulers. This, according to Lemaire, is due to “Islamic law, which was at the heart of the Ottoman administrative hierarchy,” and to the great interest the Ottoman state gave to Jerusalem. This interest increased with Ottoman concern about Western ambitions in Palestine, especially in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The documents carefully tracked by Lemaire reveal a healthy relationship between the waqf institution and the municipality during the late Ottoman period, which led to the expansion of the Abu Madyan waqf's activities to include non-Moroccans, including the poor and orphaned in the Holy City. They also reveal a series of challenges facing the waqf's work, including claims by some Ein Karem residents regarding their ownership of waqf lands, the rising influence of foreign religious institutions in Ein Karem, and the influence of foreign consulates.

In contrast, Lemaire was able to extract some features of economic and social life in Jerusalem, including: wages in Jerusalem were not rising, but the operating expenses of the Waqf remained steadily increasing; Moroccans in Jerusalem occupied supervisory and guard positions; social life was characterized by a mingling of Jerusalemites from various backgrounds and orientations, contrary to the illusions espoused by Orientalist literature; and the number of Jews in Jerusalem had increased since the beginning of the twentieth century, especially those of Ashkenazi origin, but it began to decline after they began to leave the city in 1912.

Moroccan Quarter between two world wars... approaching the time of demolition:

The entry of the British invaders into Palestine marked the beginning of the decline of the Abu Madyan Waqf, ushering in a dark phase that continued until its culmination with the demolition of the Moroccan Quarter and the displacement of its residents. The British sponsored the Zionist project coveting the Western Wall and its surrounding area, diminished the influence of the Waqf institution, reinforced the pattern of privatization, and paved the way for the erasure of a history of vitality and activity that had characterized the Moroccan Quarter for centuries.

Lemaire made an effort to monitor Zionist interest in the Moroccan Quarter. After the Jewish communities sanctified the Western Wall since the mid-sixteenth century, the Zionist project incorporated the wall and its surroundings into its program from the late nineteenth century. Attempts to purchase the quarter emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century, and the quarter's physical existence became threatened by proposals for "modernist" projects to reorganize the city starting in 1918, initiated by William H. McLean and Patrick Geddes.

The Zionist threat increased as the demand for the wall became a priority for the National Council of Palestine Jews from 1925. This was reflected in hostile acts against the neighborhood and its residents. A group of Zionists threw bombs at one of the neighborhood's houses in 1927, followed by provocative acts that led to the outbreak of the Buraq Revolution in 1929.

The French History of the Moroccan Quarter:

It was striking that Lemaire traced the French role in the history of the Moroccan Quarter, which became evident after the 1948 war. According to his explanation, many forces formulated the French position, foremost among them a “trend” in French diplomacy that sought to exploit the quarter’s need for protection and support, to show Paris to Muslims that it cared about Islamic religious institutions to the same degree that it cared about Christian institutions, in an attempt to mitigate the negative effects of its colonial policies in Algeria and the Islamic world, and to open the way for French diplomacy to play a mediating role between “Israel” and Jordan. The Orientalist Massignon was one of the most important theorists of this trend. There are also the people of the Moroccan Quarter, some of whose leaders began communicating with the French consulate in Jerusalem since 1929, presenting themselves as subjects of France, which had a duty to protect them and their property.[5] The same applies to the French authorities in Algeria, whose position was hesitant and sometimes obstructed French diplomacy, and the Jordanian administration, which was also not interested in any French role.

Since early 1949, Paris has treated the Abu Madyan Waqf as a political issue. It has been interested in the project to internationalize the holy sites in Jerusalem, based on the 1947 partition plan, with the Moroccan Quarter as the central starting point for the project. In this context, it provided aid to the Abu Madyan Waqf in the amount of 6,000 Jordanian dinars, provided by the French Consulate in Jerusalem in 1953, and held talks with the occupying state regarding the usurped lands in Ein Karem. However, this involvement suffered a setback in 1954, with the outbreak of the Algerian Revolution and the assassination of Hajj Lounis in 1957 by the revolutionaries, a key figure in the French project in the Moroccan Quarter, in addition to the negative Jordanian position. In conclusion, what the author calls the "French history" of the Moroccan Quarter is nothing more than an exceptional phase in the neighborhood's history; it was short and ineffective, and it did not achieve any results.

Moroccan Quarter: Entering the Age of Destructive People

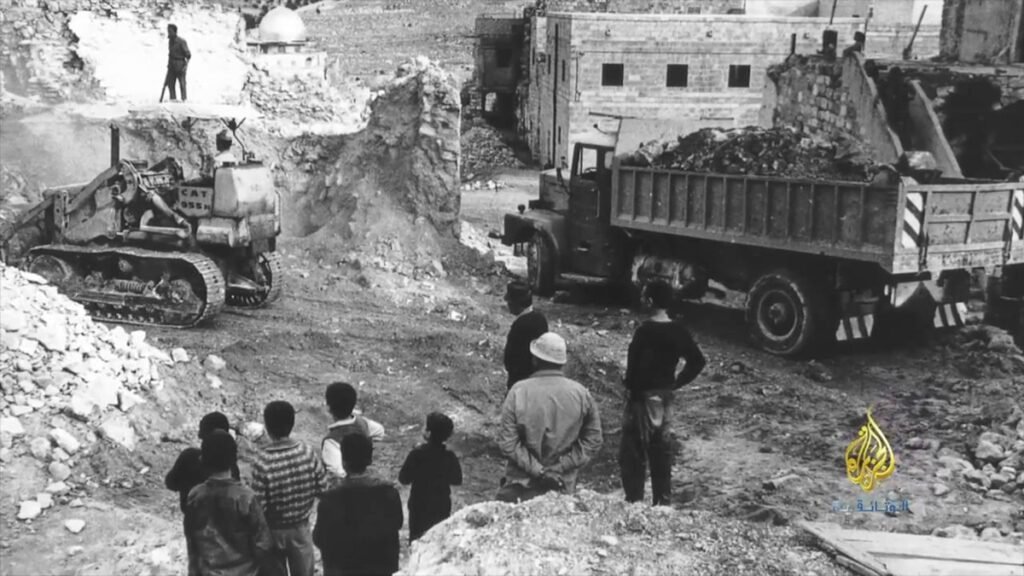

Lemaire recounts the details of the demolition of the neighborhood carried out by Israel on Saturday, June 11, 1967. He succeeds in giving us a clear picture of how the criminals made the decision to demolish it, identifying the main perpetrators of the crime, the mechanisms for its implementation, the circumstances and circumstances surrounding it, and its consequences. This is a commendable feat in light of the crime, which was not documented but rather took place out of sight. The author relies on a number of sources, including Israeli press reports, Jerusalem municipal documents, the personal archive of Miron Benvenisi, the assistant mayor of Jerusalem, oral testimonies from the neighborhood's residents, and photographs taken by French photographer Gilles Caron.

Lemerre concludes that the demolition was the result of a political decision and a "programmed, planned, and by no means spontaneous act," with the army, the municipality, and the National Parks Authority jointly responsible for its implementation. The demolition was preceded by a Zionist plan for the development of the city, launched in 1966, a year before the occupation of its eastern part. David Ben-Gurion visited the Western Wall on June 8, 1967, and emphasized the need to clear the area. The following day, a meeting was held between Teddy Kollek, the mayor, and General Uzi Narkiss to approve the demolition plan. Yosef Tekoa, of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, endorsed the demolition decision, hours before the contractors were summoned, who rushed to carry out the orders and commit the crime.

It must be noted here that the author's conclusions undermine the Zionist narrative, which is based on baseless assertions such as that the demolition initiative was spontaneous and carried out by some enthusiastic contractors, that the neighborhood was a miserable area unfit for habitation, that the departure of its residents days after the city's fall was voluntary, and that the neighborhood's dwellings negatively impacted Jewish access to the Wall. The author's conclusions confirm that the neighborhood was "an integral part of the urban space, its streets were well-maintained, and its infrastructure was regularly modernized." It is striking that Lemaire observed Western complicity in the demolition. Radio France Inter ignored the demolition of 130 homes in the neighborhood and the expulsion of 650 residents, while focusing on what it called “the freedom and independence” regained by the Israelis who were able to return to pray at the Wailing Wall. In addition, on June 14, the French consul expressed his regret for the hostility of the Palestinian Muslim population toward the Israeli forces, and considered the demolition to be accidental and intended to “clear the way for necessary access roads.”

conclusion:

The demolition of the Moroccan Quarter was not isolated from the occupation's demolition policy against Palestinian urban communities. It was preceded by demolitions that targeted hundreds of towns and villages. The occupation's appetite for demolition has not stopped since that gloomy day more than five decades ago. It has reached its peak these days in the Gaza Strip, which is subjected to a systematic process of demolition, destruction, and genocide. Although the demolition of the Moroccan Quarter took place far from human eyes, and historians needed a great effort to prove the incident/crime, what has been happening in the Strip for nearly two years is taking place within the sight and hearing of the entire world. This reveals the brutality of the enemy, the world's failure, impotence, and selfishness, the collapse of the international legal and moral system, and the severity of the suffering and oppression that the Palestinians are experiencing.

[1]The book, “The Jewish Quarter and the Moroccan Quarter in Old Jerusalem: History and Fate Between Destruction and Judaization,” was published in 2019. Al-Jubeh succeeded in tracing the history of the quarter, its people, its buildings, its activities, and its connections with the Islamic world, particularly the Maghreb, all the way to the massacre that led to its demolition and the displacement of its people. He was skilled in extracting its narrative from diverse sources, foremost among them Islamic sources:

Awni Fares,“The Jewish Quarter and the Moroccan Quarter” by Nazmi al-Jubeh: A vivid picture of the pre-1967 period“Institute for Palestine Studies Blog,” 06/10/2020.

[2] On Lemierre's research achievements and his position on the war on Gaza: Vincent Lemierre, see:

“'What is happening in Gaza is not a war to eradicate Hamas, but to eradicate civilians' • France 24“, “YouTube”, 06/14/2025.

[3] All quotes in this text are direct quotations from the book.

[4] Such as the endowment of King Al-Afdal Ali in the year 1195, and the endowment of Omar Al-Mujarrad in the year 1303.

[5] It was proposed that the French administration in Algeria take over the management of the Abu Madyan waqf properties after the 1927 earthquake, but it refused.

Quoted from: “Palestinian Studies” Journal