The "Equity and Reconciliation" Experience in Morocco: A Pioneering Model for Establishing Justice in the Arab World and Africa

introduction

At a time when many Arab and African countries are facing significant difficulties in overcoming their pasts, burdened by conflict and violations, the Moroccan experience in transitional justice stands out as an advanced model for achieving balanced and effective national reconciliation. Under the wise leadership of His Majesty King Mohammed VI, the Kingdom of Morocco has chosen an approach based on recognizing victims, providing reparations, and reforming institutions, without compromising political stability or slipping into a logic of revenge.

This experience is distinguished by its accumulation of profound lessons in managing collective memory and consolidating the rule of law, making it a model that can be adapted to other Arab and African contexts, which in turn seek to address the legacy of violations and build a democratic future based on reconciliation and justice.

Transitional justice is one of the most prominent mechanisms developed by contemporary societies to address the effects of gross human rights violations that occurred during periods of authoritarian rule or internal conflicts. International experience has shown that democratic transformation is not limited to organizing elections or drafting constitutions; rather, it requires addressing the past with political courage and moral maturity, thus strengthening trust in state institutions and enshrining the principle of non-repetition.

In this context, the Moroccan experience stands out as one of the most prominent pioneering initiatives in the Arab and African worlds, as the establishment of Equity and Reconciliation Commission The year 2004, at the initiative of His Majesty King Mohammed VI, marked a pivotal moment in the process of transitional justice in Morocco. This decision affirmed the state's commitment to the approach of reconciliation and the consolidation of values of fairness and justice, far removed from criminal penalties or narrow political calculations, with a focus on restoring the dignity of victims and redressing individual and collective harm.

The Commission based its work on an advanced legal framework inspired by international standards. It worked transparently to document the grave violations that occurred between 1956 and 1999, benefiting from the institutional support of the Advisory Council for Human Rights at the time, the positive engagement of civil society, and the involvement of the victims themselves in the process of uncovering the truth and building collective memory.

In addition to the role of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission, other institutions contributed to supporting this process, most notably: National Council for Human Rights... who followed up on the implementation of the Commission's recommendations, particularly those related to collective reparations, the integration of victims into public life, and facilitating community dialogue on reconciliation and memory, in addition to supporting legislative and institutional reforms aimed at strengthening safeguards against the recurrence of violations.

This article aims to analyze the concept of transitional justice by reviewing its theoretical dimensions, implementation mechanisms, and the challenges it faces. It highlights the Moroccan model as a pioneering experience in advanced Arab and African national reconciliation, and draws on some comparative experiences to broaden understanding of the diversity of contexts and approaches adopted across the world.

First: Conceptual foundations and emergence of transitional justice

Transitional justice is a set of judicial and non-judicial measures adopted by countries transitioning from repression or conflict to peacebuilding or democratic consolidation, with the aim of addressing gross human rights violations. These measures include criminal trials, truth commissions, reparations, institutional reform, and reconciliation mechanisms.

Transitional justice emerged in Latin America with the end of military regimes and gradually crystallized as an independent discipline within international law and human rights, particularly after South Africa's experience in overcoming the legacy of apartheid. United Nations reports, most notably the Secretary-General's Report on "The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Post-Conflict Societies" (2004), have also contributed to codifying the concept and setting international standards for it.

In this context, Morocco represents an exceptional model in the Arab world and Africa. The Equity and Reconciliation Commission was established in 2004 as the first truth commission established at the initiative of the state, rather than as a result of the collapse of its regime. This gave this experience a special dimension in terms of its dynamism and political context.

Second: The basic goals of transitional justice

Transitional justice is not merely a matter of legal accountability, but rather a comprehensive societal project in which the political intersects with the legal, and the symbolic with the institutional. Its most prominent objectives include:

Revealing the truth and building collective memory

Truth forms the backbone of any national reconciliation. Morocco's Equity and Reconciliation Commission documented cases of enforced disappearance and arbitrary detention and published a final report, considered one of the most significant documents in the history of human rights in the kingdom. This contributed to the formulation of a shared national memory based on the recognition of victims.

Establishing accountability and ending impunity

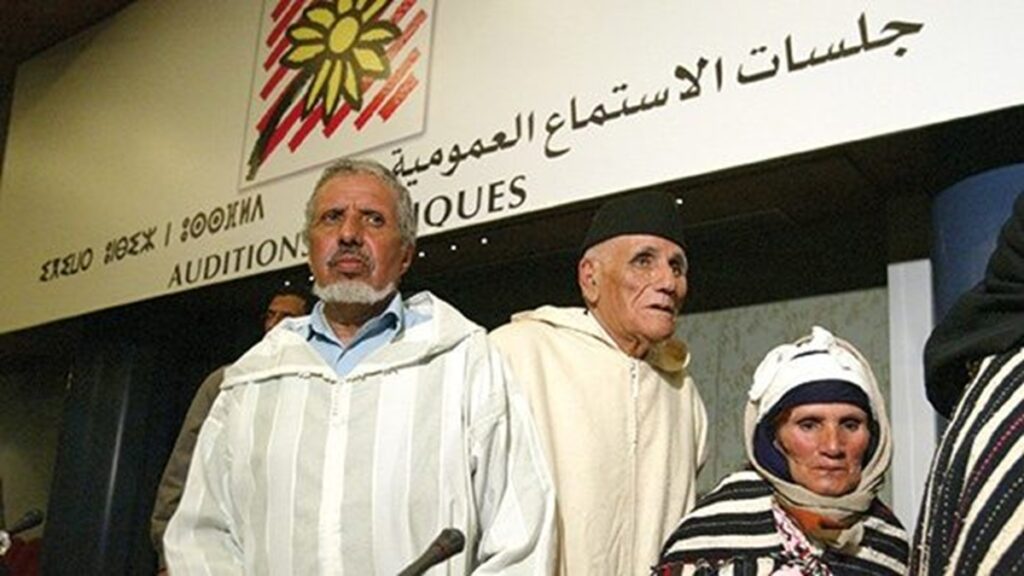

Although the Moroccan experience did not lead to judicial trials, it did carry a form of "moral and political accountability" through public hearings that Moroccans watched for the first time on television, which contributed to raising societal awareness and linking responsibility to symbolic accountability.

Victims' compensation and reparations

The Moroccan approach focused on compensating those affected, both materially and morally, through financial compensation, social reintegration, and health and psychological rehabilitation, as well as collective redress for the affected areas. This strengthened the sense of fairness and reconciliation with the state.

Institutional reform

The Equity and Reconciliation Commission recommended a series of institutional reforms, particularly in the areas of security, the judiciary, and legislation, to strengthen legal safeguards against recurrence of violations. Some of these recommendations have already been adopted, particularly regarding expanding the mandate of the National Human Rights Council and ensuring the independence of the judiciary.

National reconciliation

Ultimately, transitional justice aims to restore the relationship between state and society and achieve genuine reconciliation based on mutual recognition and respect, not on forgetting or complicity with the past.

Third: Transitional justice mechanisms

Transitional justice tools vary from country to country depending on the political and social context, but they often integrate into four main axes:

Trials

While the Moroccan experience has ruled out this option for reasons related to political balance, other countries, such as Argentina and Rwanda, have chosen trials as a central means of achieving justice, particularly in crimes of a collective nature.

Truth bodies

Morocco's Equity and Reconciliation Commission set a prominent example of such bodies, relying on investigation, documentation, and hearings from victims, and issuing practical recommendations that were not judicial in nature. It was also the first such body in the Arab world.

Compensation

The Moroccan state launched a comprehensive compensation program, covering thousands of beneficiaries. Its most prominent components included the allocation of financial funds, the provision of health and education services, and the symbolic public recognition of the victims' suffering.

Institutional reform

Transitional justice in Morocco did not stop at redressing harm. Rather, it sought to rebuild trust through reforming state institutions and strengthening human rights guarantees. This paved the way for broader societal debates about the role of the state, the limits of authority, and the concept of security.

Fourth: Challenges and constraints

Despite the importance of Morocco's transitional justice experience and its pioneering role at the Arab and African levels, it was not without difficulties and constraints that impacted some of its dimensions, both at the implementation level and in terms of societal and institutional interaction. The most important of these challenges can be highlighted as follows:

The problem between reconciliation and accountability

The balance between justice and reconciliation is problematic, as the absence of trials in the Moroccan experience is seen as one of its weaknesses, even though the approach chose to focus on building trust rather than revenge.

Limited political will

Despite the clear royal will at the time, implementing some of the commission's recommendations faced political and administrative difficulties, particularly with regard to institutional and legislative reforms.

Challenges of integrating collective memory into education and media

Despite the great symbolic and cognitive value of the outcomes of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission, their integration into educational and media policies has remained relatively limited and has not been accompanied by sufficient methodological concepts that guarantee the transfer of collective memory to new generations and the enhancement of societal awareness of the implications of reconciliation.

Fifth: Comparative experiences in transitional justice

Studying international experiences in transitional justice is essential to understanding the diversity of mechanisms and objectives, and the impact of different political and social contexts on the success or failure of these processes. The following is a brief overview of the most prominent models of transitional justice in selected countries, focusing on the specificities of each experience:

South Africa

South Africa adopted the Truth and Reconciliation Commission model, based on the principle of "amnesty for truth." Despite the controversy surrounding this model, it effectively contributed to overcoming the trauma of apartheid and building a multiracial society based on national reconciliation and mutual recognition, making it an important reference in the field of transitional justice.

Tunisia

Tunisia established the Truth and Dignity Commission to address past violations as part of the democratic transition following the 2011 revolution. However, the commission faced significant challenges, including political obstacles and deep societal divisions, which negatively impacted its effectiveness and ability to achieve comprehensive reconciliation.

Rwanda

Rwanda took a different approach by adopting traditional gacaca courts after the 1994 genocide. This model focused on community justice and local reconciliation, drawing on community traditions aimed at rebuilding the social fabric in a context radically different from Western or Arab models.

Morocco

The Moroccan model is distinguished by its relative balance between recognizing victims and maintaining political stability. With a particular focus on individual and collective reparations, institutional reform, and symbolic recognition of past tragedies, while avoiding broad judicial trials, this model has become a pioneer in the Arab and African regions and serves as an inspiration for countries seeking to address their past in a manner that balances fairness and stability.

Sixth: Transitional justice and building a democratic state

The Moroccan experience reveals that transitional justice is not a passing phase, but rather a cornerstone of building a modern state. It contributes to establishing a culture of accountability, enhancing citizen participation, and redefining the relationship between state and society on the basis of transparency and mutual respect.

Transitional justice trains societies to consciously manage their memories, not by denying or identifying with the past, but by making it a lever for building a future that embraces everyone, without exclusion or revenge.

conclusion

The Moroccan experience with transitional justice represented a pivotal moment in the political and human rights transformation process, providing a mature model for addressing past violations and building a modern state based on reconciliation and the rule of law. The pioneering role of King Mohammed VI has had a profound impact in guiding this process, through his clear support for national reconciliation and the establishment of institutional and constitutional reforms that have deepened the principles of governance, transparency, and accountability, with the goal of consolidating the rule of law.

This supreme royal political will to transform transitional justice into an effective approach to rebuilding trust between state and society and launching profound reforms encompassing legal, constitutional, and institutional dimensions has thus made the Moroccan experience in the field of transitional justice a regional benchmark to be emulated, both in the Arab and African worlds. This has highlighted the pivotal role of civil society and the lessons it holds that can be shared with countries seeking to address past violations and build a future based on reconciliation and the rule of law. These lessons can be adapted to contexts seeking justice without undermining stability, and to reconciliation as a foundation for building a democratic future.