Why doesn't Algeria like us?

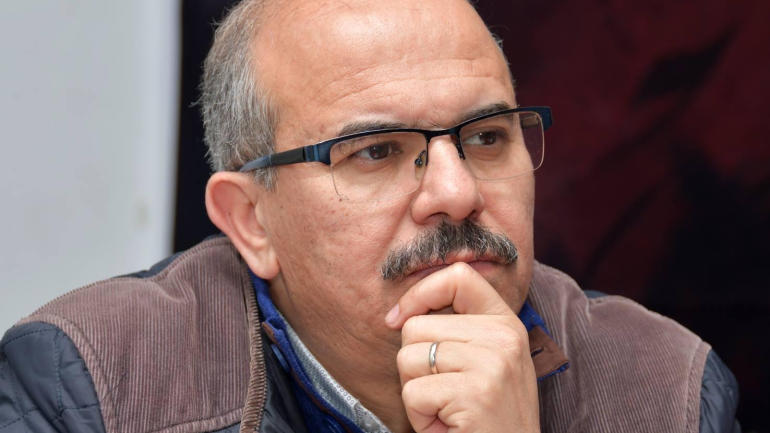

Written by: Lahcen Al-Asbi (Moroccan writer and journalist)

Is this question correct in its absoluteness?

Of course not, because it is an exaggeration, and an intentional exaggeration...

Because the purpose of presenting it is provocative, to stimulate deeper contemplation and analysis. It also implies another underlying question:

What worries Algeria about us Moroccans (the state and society)?

I'll begin with an incident that provoked my reflection as a Moroccan citizen, one I recorded with no small amount of surprise and fraternal astonishment during the month of the World Cup finals in Qatar (November 2022). It involved some of the attitudes Algerian elites at various levels fell into, clearly driven solely by the instinct of "envy," which, when it overwhelms its possessor, doesn't push them toward "competitive creativity" as much as it drags them into "negative turmoil" against themselves and others.

It was a sensation at the time for the elites who were supposed to shape public opinion in our sister country, Algeria, a sign of the extent to which the “Moroccan issue” had become negative in their subconscious. Because the semantic value (sports victory in an international forum) that Moroccan youth achieved through the techniques of fair sporting competition, unfortunately, brought out a sensational negative energy in those elites and made the disturbing question grow seriously on our reflective side.

That was a serious reason to ask another question:

Do we know Moroccan Algeria well?

It's a question of knowledge, not mere rhetoric. Indeed, it's important here that we as Moroccans question how we lack a Maghreb studies center on the same level as the "Center for African Studies." How we are academically poor in terms of possessing a solid knowledge of the structure of Mauritanian, Algerian, Tunisian, and Libyan society. We lack Moroccan experts on Algerian affairs who produce knowledge that can only be useful to every political decision-maker, in the context of the state.

In any case, it is necessary to record a preliminary observation: when we consider the above question, the report of Ms. Isabelle Werenfels, head of the North Africa and Middle East Department at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (an official institute based in Berlin), which implicitly states the (Maghreb) interest in curbing the Moroccan rise in West Africa, almost has an explanatory meaning.

In other words, as noted at the time, the German report almost sounds like it speaks for an Algerian (and, to a lesser extent, Tunisian) voice. In other words, in light of the institutional malfunctions that are hampering Algeria's development process for reasons specific to its own internal context, the rest of the peoples of the Maghreb neighborhood (especially Morocco) should pause until Algerian government policy is back on its feet, and then everyone can move freely. This is, of course, an absurd explanation, if one exists.

The unavoidable reality is that "Morocco has become a complex issue for most Algerian elites," requiring them to pay attention to the path this situation is taking them toward, for which they can only find convincing explanations in the realms of "psychology." With all that this opens (in the absence of attention and vigilance within a constructive national framework) in terms of avenues for supra-Maghreb and supra-Algerian agendas, fueling the dynamism of extremism and escalation here and there.

In the need to understand the foundations of the Algerian personality

A high-ranking Moroccan official once told me that he was shocked when an Algerian official advised him, saying:

“You Moroccans don’t understand us Algerians. Don’t respond to us, even when we’re wrong. Don’t tell us you’re wrong. That’s how we are. We don’t accept criticism.”

This reinforces an observation I have made more than once over the course of more than 40 years: when you meet an Algerian official (whether still in power or no longer), he speaks the truth directly about Moroccan territorial rights, but when he makes a public statement, he says the exact opposite.

Is it the fear of the power of the government and its military structure there?

It's actually deeper than that.

We must analytically understand, using the tools of history and political science, that what can be procedurally described as the "Algerian human community," as a newborn humanity under the umbrella of "Algerian nationalism," is experiencing a historic moment of transformation and birth, unprecedented in 100 years. This is just like a resistant plant that, through the effort of birth, strives to break through the earth's mantle and emerge into the sunshine of life, perhaps unaware of the cost of doing so, as it naturally wounds the earth in its budding and emergence and is itself wounded. In other words, every similar birth, measured by the pace of history, carries its own unique cost of pain. The wisdom in such founding moments is for this "human community," striving to deserve a "national community," to realize that its pain stems from the natural law of birth and the movement of history, and is not the deliberate act of an imaginary external actor.

It's no coincidence that a central, intriguing constant in discourse there is "monopoly," with all the implications this imposes on the intelligence of Algerian nationalism, which must be aware of the pitfalls of a similar "miserable consciousness." It's as if this "nascent self" sees the "world" as an adversary, not a partner. This is a major existential test that appeals to the intelligence of the "Algerian national consciousness."

The dominant elites remained there for years since the founding of the First Republic in 1962, governed by two central logics:

- First, the victory of the Bedouin consciousness (culture), the peasant consciousness (production structure), and the traditional consciousness (identity), through the legitimacy of the liberation gun, over all the accumulated urban partisan political elites (consciousness), commercial and labor (production structure), and modernity (culture). This is because the victor who created power out of nothing for the new state was the army as a grassroots popular structure, not the national political movement.

If we wanted to draw a graph of this, we would say that Houari Boumediene triumphed over Messali Hadj, Mohamed Aziz Jesous, and Ferhat Abbas. In other words, one culture triumphed over another.

- Second, the explosion of the certainty of "regional power," based on a discourse of "liberation legitimacy," as intangible capital, served as a bridge to create an influential presence within the calculations of international relations (during the Cold War, of course), transforming the "nascent state" into what Algeria described as "the Mecca of the world's free." This resulted in a natural clash with the ambitions of its regional neighbors, both east and west.

The result was the crystallization of two internal trends in the First Algerian Republic:

- The ruling elite's approach to building a state, which they see as having a militant legitimacy (the liberation rifle) that grants them absolute guardianship over society (the single party/single opinion), and that their historical and moral role is to "build a development model from above," under the illusion of possessing a "historical awareness" that the general public cannot grasp. Thus, power has become incompatible with or shared by anyone (an important analytical thesis on this topic was completed by French researcher René Galisseau years ago). Plans are issued from above, whether educational, industrial, agricultural, or security-related, most of which have failed in practice, leading to the emergence of some prominent figures in this field (the example of Abdel Salam Belaid, the architect of Algeria's industrialization adventure, who remained its minister for more than 10 years, culminating in the publication of his famous book "Le Hazard et l'Histoire - Chance and History" in 1990).

- The birth of a new generation of Algerian youth, who were given the opportunity to study and learn, to embark on the path of self-expression through the discourse of resistance (culturally and identity-wise), went in an exciting historical and sociological paradox in two opposing (or even contradictory) directions: a Marxist-Communist direction (the Algerian Students Union) and a conservative fundamentalist direction (with Brotherhood, Wahhabi, and Ibadi Shiite influences, intersecting with the heritage of the structure of the ancient religious zawiya, the most prominent model of which was in the Constantine region in the east and the Tlemcen region in the west).

- Over the course of thirty years (1962-1990), two internal projects crystallized, almost opposing them: the project of authority and the project of society. What unites them, at their core, is the conviction of the historically unprecedented "right to an Algerian national identity," each in its own way and with its own expressive rhetorical arsenal. The clash between the two projects led to what became known as the "Black Decade" (1992-2002). Here, it is important to return to numerous solid Algerian references to understand the contexts of what happened, including the writings of the distinguished Algerian historian Mohamed Harbi and the writings of Dr. Abdelhamid Brahimi (especially his book "On the Origins of the Algerian Crisis," published by the Center for Arab Unity Studies).

"Saddamist nationalism" as an Algerian trend

In political science, there is always a reference to two major trends in the forms of management and forms of international relations: there is the logic of hegemony and there is the logic of partnership. The choice of one of the two trends stems from the political culture emanating from the strategic managerial decision-maker in this or that country. The more democratic, pluralistic, liberal, and rights-based the ruling systems are, the more they champion the logic of partnership and cooperation. The more totalitarian, militaristic, and authoritarian the ruling systems are, the more they slide toward the logic of hegemony.

The nature of Algeria's power structure, as established since 1962, makes it certain of exercising hegemonic power within its regional sphere. Indeed, it deploys all its intelligence to create the reasons for this orientation, both at the rhetorical level (victimization and struggle) and at the management level (polarized axes policy). Consequently, unless the democratic institutional option triumphs internally within the Algerian Republic, there will be no way for the conviction of the logic of regional partnership to prevail within its ruling structure. Herein lies the disturbing pessimism regarding the nature of the ruling authority in El Mouradia Palace.

Therefore, it is legitimate to ask:

Who has changed in our Maghreb and North African region, Morocco or Algeria?

The reality today in the Maghreb is that what has changed is Morocco, having employed its national intelligence internally to achieve an institutional management overhaul, cementing a transformation within the terms of an international specifications book for the logic of the global market. This transformation is seen by some as the beginning of a "democratic transition," and many rightfully aspire to become a "democratic transformation." One of the results has been a kind of "framework" for the institutional political game within it, which has achieved two government rotations to date and further entrenched, societally, a defensive education for change using methods of "social peace" and "peaceful democratic change." This has been achieved within a strategic horizon that translates into a shift in the "state mindset," practicing politics within a "roadmap" with defined starting points and levels of capabilities, and a clear understanding of the objectives achieved as results within the logic of "state calculations."

This Moroccan change is one that the Algerian power structure has not yet accepted. Perhaps it has not grasped it or is unwilling to bear its tangible consequences on the ground.

More precisely, the elites of the first Algerian Republic do not want to realize that the logic of regional history has changed, and that they are obligated to make a smart override to achieve the logic of partnership in our Northwest African region.

Perhaps even more worrying, it is well aware that its supreme national interests as a state, as seen through the lens of 1962, are threatened, but it does not want to achieve a breakthrough by changing its approach to managing affairs with a new strategic horizon.

The challenge today is for change to occur internally, from within the structure of the "mind of power" in Algeria, because the surrounding regional and international reality is unchangeable. The reality is that today's world is one of partnership, not hegemony (regional or non-regional). Morocco has changed, the global market has changed, and African elites have changed.

Yes, Morocco has changed (despite all the challenges and malfunctions that still burden it, its defining characteristic is that it moves without stagnation, makes mistakes, and its historical destiny is to learn and overcome). It is now Algeria's turn to change with the pace of history as a new, unprecedented "national nation" for the "Algerian human community," because the greatest threat to it today is "stagnation."

Let's ask the other serious question:

Do Algerians like Morocco?

Yes, and with great sincerity. They are certain that the only side from which no harm will ever come to them is the Moroccan side.

The ball is then with the “mind of the state” of the First Algerian Republic, which must win the game of hope for an integrated, participatory Northwest African region.

There's nothing wrong with learning from each other. Every historical transcendence requires necessary sacrifices.

Link to the article on the “Anfas Press” website: